Beating a Dead Horse: The Great Depression through a Child’s Eyes

By Clark Zlotchew www.clarkzlotchew.com

(Taken from C. Zlotchew’s “Beating a Dead Horse: A Child’s Perspective of the Great Depression” published in The Abstract Elephant Magazine, June 30, 2021.)

It was a sweltering August day, and a stricken horse lay prostrate on its side in the street. When I say horses in the streets were an everyday sight in my childhood, the average millennial might assume I was born in the last decade of the 19thCentury or at least in the first decade of the 20th-Century in some small town located on the prairie. The Wild West would come to mind. However, I’m referring to the streets of New York City in the third decade of the 20th Century.

The horse in question was still attached to the vegetable vendor’s cart. It was 1938 and I was five years old during the height of the Great Depression, living in the Bronx. I don’t know if the horse had died or simply fainted with heat exhaustion. The peddler was slapping the horse in the face, yelling and cursing at the stricken animal in a futile attempt to force it to stand up. My mother explained to me that horses employed by fruit and vegetable vendors didn’t belong to the men who used them; the peddlers rented them for the day. She told me the man probably hadn’t fed the animal (it cost money and loss of time) or watered it because he wanted to cover as much ground as possible and sell all his produce as quickly as possible. The rented horse and wagon and his investment in the vegetables themselves represented a great financial risk. He could either make some profit at the end of the day, or lose money. Money, of course, represented food, shelter and clothing for the middle-aged vegetable man and his family. But my mother was just as dismayed and angry as I that the vendor could treat a dumb animal with such cruelty. Ironically, she thought the man should be horse whipped.

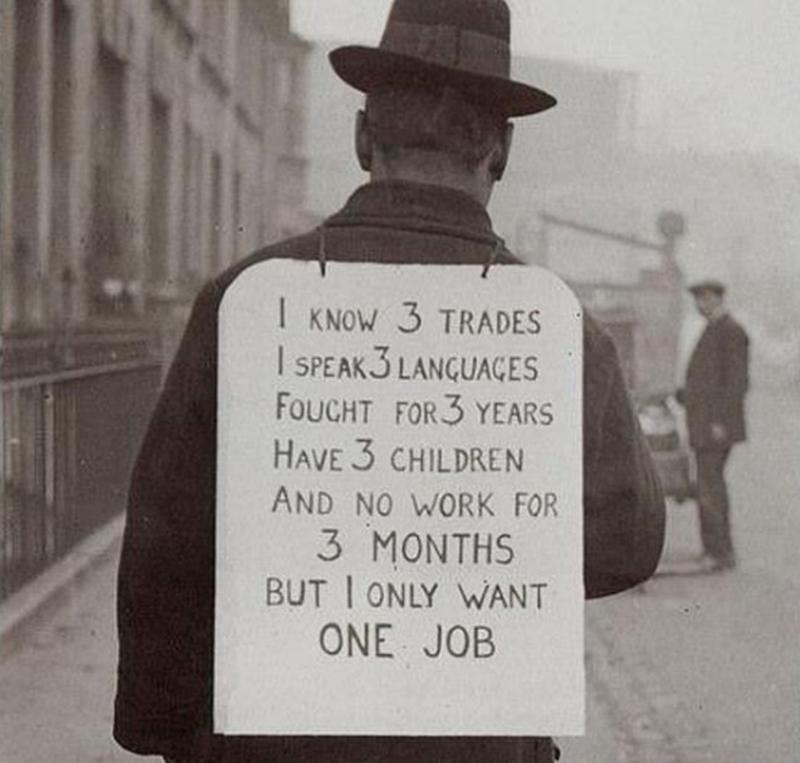

Of course, at the time I had no idea how dire the economic conditions were. Looking back, I realize we were luckier than many others in that era. My father was employed at Lazar’s, a large dry goods store located in Harlem at 125th Street and Lenox Avenue. Being employed, I now understand, was not something to be taken for granted during the Depression. Much later I learned that before my father had met my mother, he had been unemployed for a period of time. That was a phase of his life when he had to decide whether to spend a nickel for the subway to take him downtown to look for work, or to walk several miles to save the five cents in order to be able to buy something to eat at lunch time.

We lived in a three-room apartment: one bedroom, living room and kitchen. I slept on an army cot behind an upholstered chair in the living room. It didn’t seem odd to me that strangers came to our door on the second story to beg for food. My mother always gave them something. I detected a look of sadness come over her when she dealt with beggars. Also a look of fear. She kept the chain on the door fastened and passed the food to them through the small space between the door edge and the doorpost.

We had moved to the Bronx from Jersey City when I was three years old, and my mother always felt that the my birthplace (and hers) in New Jersey was inhabited by people who were completely trustworthy, whereas any part of New York City was questionable. You couldn’t tell whom you could trust or who might wish to harm you. It was a strange prejudice when you think that Jersey City is just across the Hudson River from lower Manhattan. Once, when riding a train of the Hudson Tubes under the river from Jersey City to New York, a man stood to give my mother a seat. She whispered to me, “He must be from our side of the river. A New York man wouldn’t be such a gentleman.”

In those days, many people on both sides of the Hudson shared mutual prejudices. My father’s eight sisters and brothers lived in the big City, where he too lived until he married. There was a definite feeling of superiority the New Yorkers had with regard to New Jersey people. Some of my father’s siblings remarked that my Mom was an unsophisticated “country girl.” This attitude betrays a certain provincialism, a definite lack of sophistication, on their part. The irony of the situation is heavy.

In those days it seemed perfectly normal to me that several times a week a man in the street would yell at the top of his lungs, so his voice would reach everyone in the six-story apartment building, “I cash clothes!” This meant that he would pay for used clothing, which he would later sell for a slight profit. Occasionally a man called the organ grinder would stand below the window and play a tune. People would wrap a coin in paper, to stop the coin from rolling away when it hit the sidewalk, and throw it down to the music maker who, after the tune was completed would bend down and pick up all the paper-covered coins and move on to the next building. At other times, someone on the sidewalk would play some tunes on an accordion, or a harmonica, or the ocarina, a small wind instrument popularly called the sweet potato, because of its brown color and shape. At times a man would sing well-known songs through a megaphone. The usual rain of paper-wrapped coins would ensue.

Another way to make a living during the spring and summer, was to sell fruits and vegetables by bringing them to the neighborhoods, saving people the trouble of going to stores. As a result, it was perfectly natural to see horses in the streets of New York, the big, modern, cosmopolitan city. The vendor would announce his presence by bellowing his wares in a sort of chant that somehow resembled the Muslim call to prayer. Windows were open in summer and the tenants would hear the long drawn out cry of F R E S H P E A C H E S, S T R A W B E R R I E S! or

R I P E T O M A T O E S, P O T A T O E S! People would look out their open windows and then troop down to the street to make their purchases.

Horses were such a common sight that we children took the opportunity to examine the hardworking quadrupeds when they were stopped for people to buy the produce. We noted that a horse could make its skin quiver in any area of its body when a fly would land on it in order to rid itself, however temporarily, of the annoying insect. It was just the skin, not the large muscles underneath it. We tried to imitate this action, but found it impossible to duplicate. If the fly landed on the animal’s haunches, the horse would swish its tail to shoo it away. Of course, we did not possess such an appendage and envied our four-legged friends.

We would often see a canvass bag covering the horse’s muzzle hanging by a strap on its neck. We were told the bag contained oats. This enabled the laboring beast to eat while either parked at the curb or pulling the wagon. At times we would see the animal toss its head upward. This indicated that there was a small of amount of oats left in the bottom of the bag, where the horse’s mouth could not reach. The head tossing was its technique for having the food drop into its mouth. It reminded me of the way we would place the rim of a tall glass of water or any other drink to our lips, tilt our head back and turn the glass upside down when there was still liquid in the glass, but lurking at the bottom. We were so familiar with these horses that we recognized many of them and gave them names. Throughout the summer we knew them so well that we felt they were buddies. Or at the very least, acquaintances.

The presence of so many horses on the streets of New York necessitated daily cleaning by the Sanitation Department. It was the most natural, most ordinary experience to see manure spread out on the roadways. The simple act of crossing the street was an adventure requiring a certain level of skill, equilibrium and courage. Flies constantly hovered and birds swooped down on these “road apples,” as people often called them, and were constantly in attendance to pluck specks of nourishment from the ever-present waste product. (Hence the origin of the once common slang expression, “It’s s- – t for the birds,” later reduced, for economy of language as well as for the sake of propriety, simply to “It’s for the birds.” This quaint idiom referred to any object of very little value or extremely poor quality.)

At least once daily, or perhaps twice –my memory for events of seventy five or eighty years ago is not that precise– huge tankers were slowly driven down each street. Torrents of water gushed from all sides of the tanker, washing the muck to the curbs and down into sewer openings in the curbs. A half dozen men in sparkling white uniforms followed closely behind the vehicle, three on each side of the tanker. Because much of this equine excrement had not successfully been washed into the sewers, the uniformed workers, logically known as street cleaners, using thick, broad brushes, swept the recalcitrant droppings along the curb to shove into the nearest sewer openings. This was a necessary sanitary operation which we children never tired of watching.

In those difficult times (a situation I was totally oblivious of while living through it) we had lived with my maternal grandparents and my mother’s younger siblings: her red-headed sister, familiarly called Ginger, and brother Clay. We lived with them from the time I was born in the Margaret Hague Maternity Hospital of the Jersey City Medical Center until we moved to the Bronx when I was three years old. I can still clearly picture all the rooms of the Jersey City apartment in which the seven of us lived. Horses, of course, were an important part of life there as well. If I happened to be awake at 4:00 A.M., I would hear the soft clip-clop of muffled hoof beats that announced the arrival of the milkman and his horse-drawn wagon. The sound was muffled because the hooves were outfitted in rubber horseshoes in order to avoid disturbing the sleep of customers. That soft sound at a steady beat actually soothed me back to sleep.

Later, while living in the Bronx, we would visit my maternal grandparents in Jersey City almost every weekend and on holidays. At this time my grandparents were renting the upstairs of a two-family house. There was a very large balcony that was a kind of second-floor porch. I would often sit out there and pretend I was piloting an airplane with an open cockpit. Sometimes the landlord’s daughter (we were both about seven years old) would come up to play with me. We were good playmates and friends. I remember her pretty face, curly dark hair and big brown eyes. One day we were just talking about inconsequential matters (naturally; we were just kids) when I told her to look down to the corner and across the street where there was a vacant lot. The lot was overgrown with weeds and strewn with empty tin cans. A man had led a small flock of goats there to graze. Goats in the middle of a city! It strikes me as odd now, even bizarre, but it was just another ordinary sight at the time.

Occasionally, I look back at events and scenes I remember from my childhood and find the situations are so different from those of today, that I find it difficult to believe that it was I who actually experienced those events and saw those scenes. It feels as though I’m remembering a movie I had seen, or that the person involved was someone else, but that I’ve taken over that child’s memories.

Certainly were different times. You really help me imagine them. I didn’t know how horse droppings were handled! Never even thought about it. And the origin or “For the birds” is fascinating!